The Inauguration

Tuesday, I joined the 1.8 million others on the Mall to watch the inauguration. I suppose I had underestimated just how important this event would be to the million or so people who got to the mall before I did. I had a good experience, and in retrospect a series of nearly random decisions that we made all turned out to be the right decisions.

A friend, in town and staying with us for the inauguration, and I left the house at 7 in the morning, somehow thinking that would be early enough. The station platform at the Brookland Metro was crowded when we arrived, and the inbound train that arrived was so full that only a handful more could board. We instead rode outbound one stop, thinking that either we’d catch a slightly less full train, or could get on one of the special presidential bus routes. Miraculously, there was just enough space for us on the next inbound train, which otherwise looked as crowded as the first.

We managed to meet a bunch of my friend’s friends downtown, at their hotel, at 8. We were north of the mall. Since all of the parade route along Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol to the White House was walled off, we had to choose a route south. Among the many roads closed to motor traffic that day was 395, the freeway in a tunnel that goes under the Capitol reflecting pool. It was open as a pedestrian route, and in part because of the novelty of walking it, that’s were we went. Later, we heard that the handful of crossovers through the parade route became impossibly backed up. We entered at about 3rd and G NW and exited at E Street SW. We made our way along E, then up 7th to D, then along D to 14th, where we crossed into the Mall, finding spots at the base of the Washington monument by about 9am.

And then we waited, in the cold. A half hour of relative stillness was enough to take away the warmth that physical movement generates, and I was reminded how much colder it is when you’re not moving. I knew this, but hadn’t really thought about how long we’d be out there. As was widely recommended, I had layered, and soon wished I had layered more. Perhaps what one should do is to subtract ten degrees Fahrenheit from the actual temperature for every hour you’ll be standing in the cold.

We had a decent view of a Jumbotron, and we could see the Capitol, but even with binoculars I couldn’t see any individuals. (Our view was partially blocked by trees.) What was significant was to be a part of the 1.8 million assembled, and of the 1.12 million Metro rides that day. It occured to me, standing there, that one had to understand what was going on in order to get anything out of the experience. I was glad that my son was safely and warmly at home; to be able to tell him in later years that he was there would have been a useless gimmick.

So what did I understand the experience to be? On the one hand, under the former administration, I (in chronological order): earned my Ph.D., got a permanent research job, got married, bought a house, had a child. Am I better off than I was eight years ago? Unquestionably, yes. Not bad for living a few miles from the epicenter of what was quite possibly the worst administration in United States history. But of course I was out there in the cold, celebrating with everyone else.

The president has called upon Americans to rise up to our nation’s challenges. He is not the first to call for service to our country and to others, but unlike the mawkishly sanctimonious appeals of virtually every other public leader, his carry a sincerity and gravitas that is convincing. This is perhaps because of his extensive service as a community organizer. As hope and competence replace fear and cronyism as dominant motifs in the administration, I expect that the appeal of satire and detached irony will fade in popular culture: these are for those who are comfortable, detached, and powerless. Anger and self-absorbed drama are out; hard work and careful planning are in. Does this signal an ascendancy for The University of Chicago? The President taught there, of course. David Axelrod, chief campaign stategist, went there, as did Nate Silver, whose reality-based analysis beat all the other pundits this time around.

Four years ago, the progressive blogosphere wanted everyone to read Don’t Think of an Elephant, and now we have a progressive President that has intuitively understood framing and the use of language longer and better than anyone else on our side. Democrats should now be done with Triangulation. And Mark Penn and Terry McAuliffe, too.

On energy and environment and global warming and scores of other policies, Obama can already be said to be turning things around. Although Obama is not the first to mention science in his inaugural address, his reversal of the previous administration’s anti-scientific outlook is heartening. Perhaps our nation can be done with the celebration of anti-intellectualism. Perhaps patriotism will no longer be associated with flag-waving belligerence, but will be understood instead to be a celebration of those extraordinary characteristics of our nation that made our President’s story possible.

This was my hope, as I stood in the cold on the National Mall last Tuesday.

January 27, 2009 1 Comment

Red Street, Blue Street

In the end, I went with the upgrade to Mathematica 7. Of all the new features, the one that really hooked me–which is comparatively minor, compared to all the other new features–is the ability to import SHP files. The importation is not terribly well documented nor is there much additional support, but it was pretty easy to do a few nifty things with the DC Street Centerline file.

As you may know, there is a street in DC for every state in the union. Pennsylvania Avenue is probably the most famous of these; the White House sits at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW. I used to live on Massachusetts Avenue. So my first idea was to make a street map of DC in which the state-named streets were colored red-ish or blue-ish depending on their vote in the recent election.

Here it is:

Read on to see how I made it:

January 17, 2009 1 Comment

Bringing streetcars back to DC, part 3

Parts 1 and 2 of this series looked at the public side of the DC Alternatives Analysis process that took place between 2002 and 2005. Several newsletters were published, public meetings were held, and the study team met with civic groups and maintained a presence at various community events. The widely distributed documents only tell a small fraction of the story, and if one wants to understand why the final report had such disappointing recommendations, one needs to delve into the more technical study documents, which weren’t widely distributed. The contrast between that which was published publicly and the technical documents kept internally is instructive for anyone following a similar engineering study of similar scale.

Broadly speaking, these technical documents attempt to quantify the decision-making process in order that every subsequent decision have justification. The process obscures the study biases by shifting them into the methods of quantification, and ultimately confuses quantifiability with importance.

Setting the Stage

The formal program of the study was documented in the Project Work Plan, in January 2003. One of the first of the study documents was the short Quality Assurance Program, an eight-pager released in November 2003. It establishes the tedious tone in which all further study documents will be written with empty management-speak such as “All DMJM Harris staff performing tasks on the project will utilize the appropriate implementing procedure for the work being performed.”

Two reports were finished in August 2004: The Needs Assessment and the Evaluation Framework. These followed the extensive series of community meetings in late 2003. The Needs Assessment was the only technical document that was published on the (now-defunct) study website. It examined population, employment, and overall destination patterns across the city in relation to existing transit service. The Evaluation Framework brought together all the input–from DC agencies and from the community–about routes and goals and needs and defines what sort of analysis is to be done. A structure of seven routes is proposed, two of which have alternative routings, but the stops along those routes are not defined yet. The project goals are laid out, and the measures and criteria used to evaluate choices in terms of those goals are defined. The general work plan for several documents that follow is laid out.

Route and Mode evaluation:

Screen 1, released September 2004, evaluates seven potential transit modes (streetcars, “bus rapid transit,” light rail transit, diesel multiple units, automated guideway transit, monorail, and heavy rail), and ends up recommending only streetcars and “bus rapid transit” for further evaluation.

The Definition of Alternatives, released in November 2004, analyzed the routes given in the Evaluation Framework for the two chosen modes. Station locations were assigned and propulsion technologies are considered. For each route, a “service plan” was developed, including the headways between successive runs and calculations for route travel times. Although there are separate calculations for streetcars and for “bus rapid transit,” no details are given about the assumptions that went into the calculation of the travel times.

Screen 2, released March 2005, takes the service plans and route structure from the Definition of Alternatives and tries to evaluate how well each would fulfill the project goals by applying a set of “Measures of Effectiveness,” which are defined in the Evaluation Framework. Claiming that “the operational characteristics of BRT and Streetcar are similar at the level of detail” under study, it lumps both into a “premium transit service option” to decide whether a particular corridor should have “premium transit,” or whether it should only receive some bus service enhancements. Corridors were ranked (high, medium or low) based on a few criteria for each of the four project goals, leading to a composite score. Further analysis on meeting corridor deficiencies and operational considerations, and concluded by recommending some routes for “premium transit” and relegating some to get only “local bus enhancements.”

Screen 3, released May 2005, takes the “premium transit” corridors of Screen 2 and applies further “Measures of Effectiveness” to determine whether each corridor should be Streetcars or “bus rapid transit.” Each corridor is broken into segements, and the effectiveness criteria are applied to the segments individually. Where applicable–which isn’t as frequently as one might think–Streetcars and “bus rapid transit” are evaluated separately. The scores from these evaluations are totaled, to come up with proposals for streetcar routes, “bus rapid transit” routes, and “rapid bus” routes.

And onwards

Further study documents, released May–September 2005, looked at the finances of the proposed system and put forward the timetable. All the study findings were summarized in a final report, published in October 2005. Future posts in this series will look in detail at some of these technical reports.

December 15, 2008 No Comments

Matthew’s Books updated

I keep a permanent page on this website listing the books that my son has, in order to minimize duplicate copies. I have just now updated this list to include books acquired over the past year.

He does also have a number of books in Korean, which are not presently listed.

December 4, 2008 No Comments

The next Mathematica

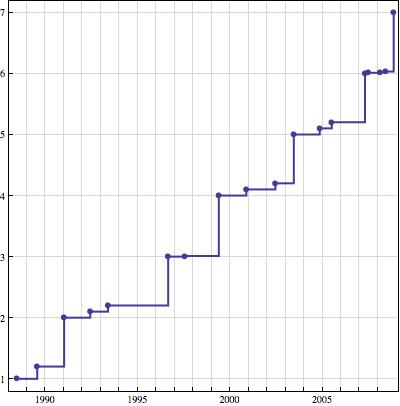

To me, an intermediate and somewhat casual Mathematica user, the news that Mathematica 7 had been released was a surprise. Surprising to me because Mathematica usually goes much longer between major-digit releases; I would have anticipated this to be Version 6.1. For fun, I’ve plotted the history of Mathematica versions1 :

Release dates of versions of Mathematica

Mathematica 6 was a substantial upgrade: the graphics system was completely overhauled, the curated data, that I’ve used as the basis for some posts here, was added, and the ability for dynamic interactivity was added with Manipulate and Dynamic.

I am not, of course, a major Mathematica user. In fact, although I’m a physicist, I haven’t made tremendously much use of Mathematica for my professional work. This is partly because I tend to deal with relatively small data sets, for which a GUI-based data analysis tool is usually easier to work with than the command-line Mathematica. And I’d consider myself an advanced user of Pro Fit, the data analysis tool that’s made all the graphs for all the work I’ve done since about 1998.

In fact, my Mathematica license is my own personal one. As a graduate student, I bought the Student version of Mathematica, which they allow you to upgrade to a full professional license for only a few hundred dollars, compared to the $2500 list price of a new professional license.

Wolfram really wants its users to buy Premier Service, a several hundred dollars per year service which entitles you to all upgrades, major and minor. If you don’t buy premier service, then you need to pay for all upgrades, even the N.M.X to N.M.X+1 minor bug-fixing upgrades. And without premier service, you’re not even supposed to install Mathematica on more than one computer. Draconian and greedy, if you ask me, but they can do that, because they’re Wolfram. And for tech-heavy firms that make heavy use of Mathematica and get millions of dollars worth of value from whatever they compute in Mathematica, it makes sense. But it makes it very difficult to be a casual user.

And even though your existing copy can do everything it could the day you bought it, once the difference between your copy and the current release gets large enough, there is no longer an upgrade path. I think this is one of the motivations to release this as version 7 and not 6.1: I don’t recall the precise figure, but Wolfram generally offers an upgrade path only for jumps smaller than 1.5. If this is still the case,2 what this does is cut off anyone who hadn’t upgraded to version 6. Update: enough with the conspiracy theories! Wolfram clears up the upgrade policy in the comments.

In my case, with Version 6.0.1, I have a choice of paying $750, and getting a year of Premier Service, or paying $500 for just version 7.0.0 with no service. Out of my own pocket, ouch! But what makes it really enticing, for me, is that Mathematica now reads SHP files. These are the Geographic Information System data files, promulgated by ESRI, in which vector-valued geographic data is commonly exchanged. In particular, the DC Office of Planning makes an amazingly large collection of DC GIS data available in SHP format. The possibility for quantitative analysis of DC mapping data is very tantalizing.

Of course, Wolfram wouldn’t release a major number upgrade without hundreds of other new features. As of yet, there isn’t much substantial written about version 7. I did find some notes from a beta-tester and from a college math teacher. I’ll probably buy it, even though it would mean delaying other expensive toys that I want.

- most of the dates come from the Wolfram News Archive, some from the Mathematica scrapbook pages [↩]

- I’ve asked Wolfram, but haven’t received a reply. [↩]

November 22, 2008 3 Comments

Twenty megawatts in your hands

I needed to buy more gasoline for the car today, and I decided to see how long it took to fill the tank. I bought ten and a half gallons of gas, and it took 70 seconds to fill it up. Although filling up a gas tank is something that millions of Americans do every day, it’s really remarkable when you stop and think about the energy transfer going on.

Gasoline has, approximately, 113,000 BTUs per gallon.1 One BTU is 1055 Joules. So I transferred 1.25 Billion Joules in those 70 seconds, which is a rate of 17.9 megawatts. When you consider that you spend less than two minutes pumping the same amount of energy you burn in four hours of driving, it’s not surprising that you end up with such a high power. What’s more interesting, I think, is to contemplate the rather fundamental limits this puts on plug-in electric cars.

Internal combustion engines, according to Wikipedia, are only about 20% efficient, which is to say, for every 100 BTUs of thermal energy consumed by the engine, you get 20 BTUs of mechanical energy out. This is, in large part, a consequence of fundamental thermodynamics. Although electric motors can be pretty close to perfectly efficient, a similar thermal-to-electric efficiency hit would be taken at the power plant.

Let’s consider, then, that we want a similar car to mine, but electric. Instead of 1.25 gigajoules, we need to have 250 megajoules. Battery charging can be pretty efficient, at 90% or so, which means we’d supply 280 megajoules. If we expect the filling-up time to be comparable to that of gasoline cars–call it 100 seconds for simplicity–then we’d need to supply 2.8 megawatts of power. At 240 Volts, which is the voltage we get in our homes, this would require 11700 amps; if you used 1000 Volts, it would take 2800 amps. Although equipment exists2 to handle these voltage and current levels, it is an understatement to say that it cannot be handled as casually as gasoline pumps are handled. Nor is it clear that any battery system would actually be able to accept this much power.

A linear relationship exists between the power requirement for filling, and the vehicle range, the vehicle power, and the time for a filling. If you’re satisfied with half the range of a regular vehicle, for example, you could use half the filling power. Let’s imagine that you’d be happy for the filling to take ten times as long as with gasoline, or 1000 seconds, just under 17 minutes. At this level, you’d need 280 kilowatts of power. If battery charging is 90% efficient, that means 10% of the power is going to be dissipated as heat, which in this case would be 28 kilowatts.

For comparison, a typical energy consumption rate for a home furnace is 100,000 BTU per hour, about 28 BTU per second, or 29.3 kilowatts. Which means that the waste heat dissipated during charging for the example–of a 1000 second fill for a vehicle with similar range and power as a modest gasoline powered sedan, at 90% charging efficiency–is as much as the entire output of a home furnace.

No wonder overnight charges are the standard.

- Summer and winter blends have slightly more and less, respectively. [↩]

- think about how large the wires would need to be [↩]

November 13, 2008 4 Comments

Bringing Streetcars back to DC, part 2

Part 1 of this series looked at the beginnings of the DC government’s effort to expand the transit network. We left off in the Spring of 2005, having been to several meetings and having received several newsletters.

The study finishes

The final project newsletter, Fall 2005, and an “Executive Summary” of the whole project were presented to the public at a final meeting, held September 29, 2005. For transit enthusiasts following the project, the end results were disappointing and frustrating. Instead of a visionary transformation of mobility in the District, the final recommendations proposed a meager streetcar buildout that, despite its modest size, would take 25 years to build. The report was frustrating because it relied on tortured reasoning that bordered on downright dishonesty, it used self-contradictory and mutually inconsistent reasoning, and offered little more than poorly-defined chimeras wrapped up in wishful thinking.

Added to the project was “Rapid Bus,” as a lower-class technology mode, joining streetcars and “bus rapid transit.” Modes were assigned to routes. The newsletter used separate streetcar and “bus rapid transit” assignments, while the executive summary lumped these together as “premium transit.” In the newsletter, streetcars got a handful of routes: the crosstown Georgtown to Minnesota Avenue route; the north-south Georgia Avenue route, which would end at K street; a Union Station to Anacostia via Eastern Market route; an M Street SE/SW route, and a short Bolling AFB–Pennsylvania Ave route. A bit of “bus rapid transit” was added: mainly Woodley Park to Eastern Market via Florida Avenue, while the rest of the 50-mile route structure developed over the course of the study was designated “rapid bus.”

November 9, 2008 1 Comment

Dow Jones and Mathematica

A recent post by economist-blogger Brad DeLong, which was also picked up Matthew Yglesias, mused upon the clustering of the Dow Jones Industrial Average clustered near values starting with 1. He showed a chart with the years 1971–1984, and 1996–2008 circled, when the Dow appeared to fluctuate near 1000 and 10000, respectively. Many commenters quickly jumped to point out that this was an example of Benford’s Law, which says, essentially, that if you’re throwing darts at a logarithmically shaped dartboard, you’re going to hit “1” more often than any other digit. If you pick random values of some phenomenon that is logarithmically distributed, you should get values beginning with “1” about 30% of the time, which makes sense if you’ve ever looked at log scale graph paper.

It occurred to me that this is an easy thing to investigate with Mathematica, much like my earlier post on the Bailout. Mathematica 6 includes access to a huge library of curated data, including historical values of the Dow Jones Industrial average and other indices (and individual stocks, and so forth). The function here is FinancialData, which Wolfram cautions is experimental: I believe they get the data from the same source as, say, Yahoo! Finance, and just do the conversions to make it automatically importable into Mathematica. That is, it is no more reliable than other web-based archives. The computations are absurdly easy, taking only a few lines of Mathematica code.

The graph I (eventually) produced shows the relative frequencies of first digits that are calculated by Benford’s Law, together with the relative frequencies of the leading digits from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500, the NASDAQ Composite index, the DAX 30, and the Nikkei 225:

November 1, 2008 No Comments

Bringing Streetcars back to DC, part 1

Prologue

Bringing a 50-mile streetcar network to Washington DC is the top priority for the DC Chapter of the Sierra Club. I have been following this issue with the Sierra Club since 2002, and it was recently suggested to me that I write down a brief history of the effort, to provide context for those new to the subject. Current progress on the issue is blogged at streetcars4dc.org.

The DC Transit Improvements Alternatives Analysis gets underway.

The last time streetcars ran in DC was the early morning of January 28th, 1962, after which all lines were converted to buses. Such was the state of public transit in the District until March 27, 1976, when Metrorail opened. Metrorail, of course, has been a tremendous success, but it does not serve all areas of DC, and was designed primarily to move suburban commuters to their jobs in downtown DC.

The District government has, in principle, been planning to bring streetcars back to DC for some time now. My involvement began in September 2002, when I testified on behalf of the at a joint oversight hearing of the DC City Council. A relatively small, two-year study had recently been completed (DC Transit Development Study), and then-DDOT director Dan Tangherlini, and then-DDOT Mass Transit Administrator Alex Eckmann went before the council (read their presentation) to ask that a more expansive study be funded. Plans to expand transit in the District stretch back further than that, and are generally said to have begun with the Barry-era DC Vision Study of 1997, itself 2 years in the making. And after more than ten years of talk and study, there are still no streetcars.

October 29, 2008 2 Comments

My new line for telemarketers

I actually don’t talk to many telemarketers anymore–I’m on the do not call list, so nobody’s been calling to sell me aluminum siding or vacation get-aways. Ever since cell phones really took off, it seems that the long distance companies aren’t falling over themselves to get you to switch to their plan, although I do remember plenty of this in the late 90’s. And although we don’t have caller ID, we’ve gotten pretty good about catching the second or so delay from the robodialers and hang up before the telemarketer comes online.

But sometimes someone does get through, and it’s usually either a charity (usually one that I nominally support) or a political campaign, asking for more money. However, I really, strongly prefer to give on my own terms and on my own schedule, and not theirs. So I want to get rid of them, in some way that’s still polite. So this is what I say now:

Although I will continue to support [your cause], I do not make financial commitments over the phone due to identity theft concerns.

All I have to do now is think of a line to get rid of the (overpriced) identity theft “protection” sales pitches that my credit card companies foist upon me.

October 21, 2008 1 Comment